Intel To Wind Down Optane Memory Business – 3D XPoint Storage Tech Reaches Its End

It appears that the end may be in sight for Intel’s beleaguered Optane memory business. Tucked inside a brutal Q2’2022 earnings release for the company (more on that a bit later today) is a very curious statement in a section talking about non-GAAP adjustments: In Q2 2022, we initiated the winding down of our Intel Optane memory business. As well, Intel’s earnings report also notes that the company is taking a $559 Million “Optane inventory impairment” charge this quarter.

Taking these items at face value, it would seem that Intel is preparing to shut down its Optane memory business and development of associated 3D XPoint technology. To be sure, there is a high degree of nuance here around the Optane name and product lines – which is why we’re looking for clarification from Intel – as Intel has several Optane products, including “Optane memory” “Optane persistent memory” and “Optane SSDs”. None the less, within Intel’s previous earnings releases and other financial documents, the complete Optane business unit has traditionally been referred to as their “Optane memory business,” so it would appear that Intel is indeed winding down the complete Optane business unit, and not just the Optane Memory product.

Update: 6:40pm ET

Following our request, Intel has sent out a short statement on the Optane wind-down. While not offering much in the way of further details on Intel’s exit, it does confirm that Intel is indeed exiting the entire Optane business.

We continue to rationalize our portfolio in support of our IDM 2.0 strategy. This includes evaluating divesting businesses that are either not sufficiently profitable or not core to our strategic objectives. After careful consideration, Intel plans to cease future product development within its Optane business. We are committed to supporting Optane customers through the transition.

Intel’s associated 10-Q filing also contains a short statement on the matter.

In the second quarter of 2022, we initiated the wind-down of our Intel Optane memory business, which is part of our DCAI operating segment. While Intel Optane is a leading technology, it was not aligned to our strategic priorities. Separately, we continue to embrace the CXL standard. As a result, we recognized an inventory impairment of $559 million in Cost of sales on the Consolidated Condensed Statements of Income in the second quarter of 2022. The impairment charge is recognized as a Corporate charge in the “all other” category presented above. As we wind down the Intel Optane business, we expect to continue to meet existing customer commitments.

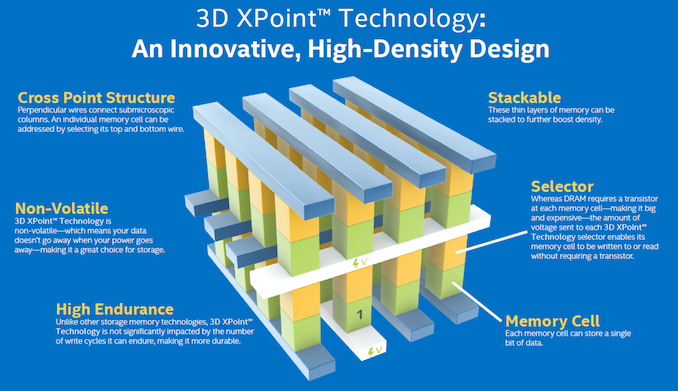

First announced by Intel in 2015, the company’s 3D XPoint memory technology was pitched as the convergence between DRAM and solid state storage. The unique, bit-addressable memory uses phase change technology to store data, rather than trapping electrons like NAND technology. As a result, 3D XPoint offers incredibly high endurance – on the order of millions of writes – as well as very high random read and write performance since its data doesn’t have to be organized into relatively large blocks.

Intel, in turn, used 3D XPoint as the basis of two product lineups. For its datacenter customers, it offered Optane Persistent Memory, which packaged 3D XPoint into DIMMs as a partial replacement for traditional DRAMs. Optane DIMMs offered greater bit density than DRAM, and combined with its persistent, non-volatile nature made for an interesting offering for systems that needed massive working memory sets and could benefit from its non-volatile nature, such as database servers. Meanwhile Intel also used 3D XPoint as the basis of several storage products, including high-performance SSDs for the server and client market, and as a smaller high-speed cache for use with slower NAND SSDs.

3D XPoint’s unique attributes have also been a challenge for Intel since the technology launched, however. Despite being designed for scalability via layer stacking, 3D XPoint manufacturing costs have continued to be higher than NAND on a per-bit basis, making the tech significantly more expensive than even higher-performance SSDs. Meanwhile Optane DIMMs, while filling a unique niche, were equally as expensive and offered slower transfer rates than DRAM. So, despite Intel’s efforts to offer a product that could crossover the two product spaces, for workloads that don’t benefit from the technology’s unique abilities, 3D XPoint ended up being neither as good as DRAM or NAND in their respective tasks – making Optane products a hard sell.

As a result, Intel has been losing money on its Optane business for most (if not all) of its lifetime, including hundreds of millions of dollars in 2020. Intel does not break out Optane revenue information on a regular basis, but on the one-off occasions where they have published those numbers, they have been well in the red on an operating income basis. As well, reports from Blocks & Files have claimed that Intel is sitting on a significant oversupply of 3D XPoint chips – on the order of two years’ of inventory as of earlier this year. All of which underscores the difficulty Intel has encountered in selling Optane products, and adding to the cost of a write-down/write-off, which Intel is doing today with their $559M Optane impairment charge.

Consequently, a potential wind-down for Optane /3D XPoint has been in the tea leaves for a while now, and Intel has been taking steps to alter or curtail the business. Most notably, the dissolution of the Intel/Micron IMFT joint venture left Micron with possession of the sole production fab for 3D XPoint, all the while Micron abandoned their own 3D XPoint plans. And after producing 3D XPoint memory into 2021, Micron eventually sold the fab to Texas Instruments for other uses. Since then, Intel has not had access to a high volume fab for 3D XPoint – though if the inventory reports are true, they haven’t needed to produce more of the memory in quite some time.

Meanwhile on the product side of matters, winding-down the Optane business follows Intel’s earlier retreat from the client storage market. While the company has released two generations of Optane products for the datacenter market, it never released a second generation of consumer products (e.g. Optane 905P). And, having sold their NAND business to SK Hynix (which now operates as Solidigm), Intel no longer produces other types of client storage. So retiring the remaining datacenter products is the logical next step, albeit an unfortunate one.

Intel’s Former Optane Persistent Memory Roadmap: What WIll Never Be

Overall, Intel has opted to wind-down the Optane/3D XPoint business at a critical juncture for the company. With their Sapphire Rapids Xeon CPUs launching this year, Intel was previously scheduled to launch a matching third generation of Optane products. The most important of these was to be their “Crow Pass” 3rd generation persistent DIMMs, which among other things would update the Optane DIMM technology to use a DDR5 interface. While development of Crow Pass is presumably complete or nearly complete at this point (given Intel’s development schedule and Sapphire Rapids delays), actually launching and supporting the product would still incur significant up-front and long-term costs, as well as requiring Intel to support the technology for another generation. Giving Intel a strong incentive to finally take an exit on the money-losing business unit.

In lieu of Optane persistent memory, Intel’s official strategy is to pivot towards CXL memory technology (CXL.mem), which allows attaching volatile and non-volatile memory to a CPU over a CXL-capable PCIe bus. This would accomplish many of the same goals as Optane (non-volatile memory, large capacities) without the costs of developing an entirely separate memory technology. Sapphire Rapids, in turn will be Intel’s first CPU to support CXL, and the overall technology has a much broader industry backing.

AsteraLabs: CXL Memory Topology

Still, Intel’s retirement of Optane/3D XPoint marks an unfortunate end of an interesting product lineup. 3D XPoint DIMMs were a novel idea even if they didn’t quite work out, and 3D XPoint made for ridiculously fast SSDs thanks to its massive random I/O advantage – and that’s a feature it doesn’t look like any other SSD vendor is going to be able to fully replicate any time soon. So for the solid state storage market, this marks the end of an era.